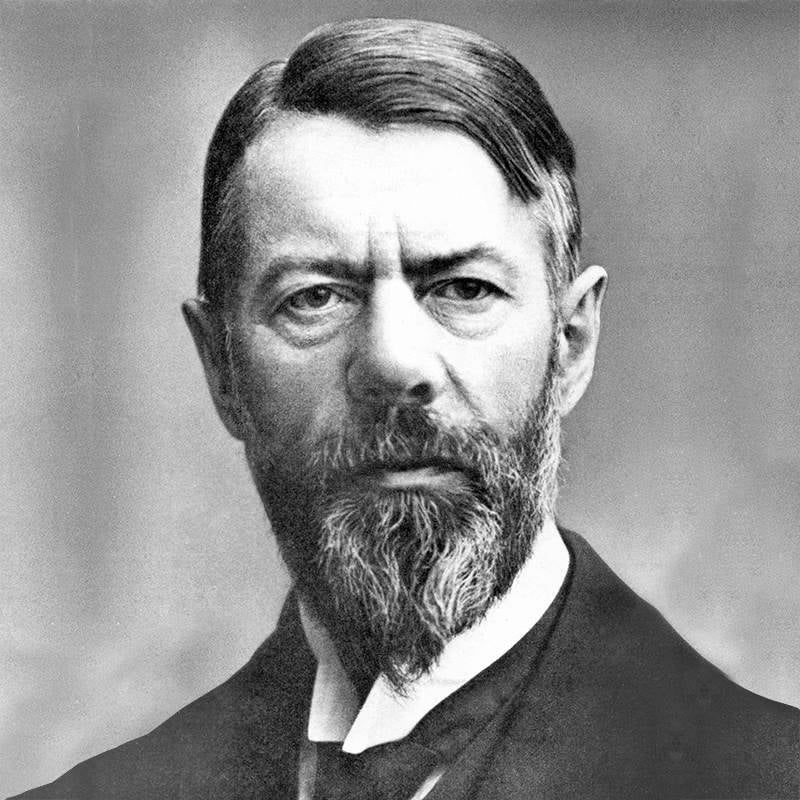

Max Weber

"Our highest ideals forever affect in conflict with other ideals,

that are as sacred to others, as ours are to us."

"Every action and inaction means taking sides in favor of certain values and against others.

It's up to us to make the choice."

- Max Weber

An overview of Weber's work

Max Weber defined sociology as a science that aims to understand and causally explain social actions. It seeks to interpret social behavior and clarify its course and consequences. Weber distinguished between the natural sciences (e.g., physics) and the cultural sciences (e.g., sociology). He highlighted the need for understanding and empathizing (Verstehen) with human behavior in cultural sciences; researchers should try to understand individuals' actions and motivations.

Weber introduced ideal types, which are theoretical constructs used to systematize and compare elements of reality. They are not ethical ideals but serve as analytical tools to simplify complex social phenomena.

Weber discussed the challenge of maintaining value neutrality in scientific research. While personal values may influence research choices, he argued that researchers should avoid allowing their values to bias the interpretation of research findings.

An important subject in Weber's work is the process of rationalization in society, where rational, goal-oriented action becomes more prevalent and traditional, affective, and traditional actions are marginalized. He examined the rise of bureaucracy in modern society, emphasizing its efficiency and rational organization, while also noting its potential dehumanizing effects.

According to Weber, Protestantism, particularly Calvinism, and the development of the spirit of capitalism are connected. He argued that certain religious values, such as the idea of a calling and asceticism, contributed to the rise of capitalism.

Charismatic leadership was also studied by Weber. It involves leaders with extraordinary qualities who emerge in times of crisis. Charismatic authority can be transformative but is often temporary. Charismatic authority can be routinized and transformed into traditional or legal-rational authority over time. But, charismatic groups often reject economic rationalization, emphasizing spiritual values over material gain. This can lead to celibacy and communal living. Weber's ideas on charismatic leadership remain relevant in the study of contemporary charismatic religious and social movements.

Weber's impact

Max Weber (1864-1920) has probably had the biggest impact on modern sociology from all German sociologists. Central to Weber is the development of a multitude of concepts and conceptual combinations in sentence form, which must be tested as hypotheses against the data or facts, i.e. against the statements about observed properties of a concrete phenomenon. This makes him, together with Emile Durkheim, the founder of sociology as a positive science. Weber thus saw sociology as a science that seeks to understand social action in a value-free way and to explain its more or less probable multiple causes. Cultural content can only be clearly reduced as intended for religious sects, not in any other way.

Rationalization

Weber saw in our modern time an increase in goal-rational action and a decrease in value-rational and traditional action. This can be seen as an elaboration of the terms Gesellschaft and Gemeinschaft of his contemporary Ferdinand Tönnies. Weber's rationalization is characterized by computability, efficiency, predictability, non-human technology, control over uncertainties, and irrational consequences for the individuals involved.

Weber fought against the in his lifetime common blood and race mysticism. With his existential rationalism, he created a real ethics of everyday behavior, an everyday morality that is independent of a specific zeitgeist. For him, the attitude of perseverance, of testing, of criticism, of skepticism against all cheap religious or aesthetic irrationalism is the actual path to human emancipation in the sense of real freedom.

The Protestant Ethic

According to Weber, Calvinism encouraged the development of a capitalist mentality by promoting the idea that hard work, frugality, and the accumulation of wealth were signs of God's favor. Calvinists were encouraged to work hard and be productive in their economic endeavors as a way to demonstrate their faith and demonstrate that they had been predestined for salvation. Weber argued that this "Protestant ethic" contributed to the development of modern capitalism and the capitalist economic system.

Weber himself did not argue that one religion or culture is inherently superior to another. Instead, he argued that certain religious beliefs and practices may be conducive to the development of certain economic systems.

Below are some quotes from Weber's most significant works:

Ethics of responsibility

"Since we can (within the respective limits of our knowledge) validly determine which means are suitable or unsuitable for achieving an imagined end, we can in this way weigh the chances of attaining an end at all with certain available means and thus indirectly criticize the purpose itself, based on the respective historical situation, as practically meaningful or as meaningless given the state of affairs. Furthermore, if the possibility of achieving an imagined goal appears to be given, we can of course always within the limits of our respective knowledge, determine the consequences which the application of the necessary means would have in addition to the eventual achievement of the intended goal, as a result of the overall context of all events. We then offer the actor the opportunity to weigh up these unintended against the intended consequences of his actions and thus answer the question: what does it cost to achieve the desired purpose in the form of the likely violation of other values? Since in the vast majority of all cases every desired end in this sense costs something or at least can cost something, no self-reflection of responsible acting people can ignore the weighing up of the purpose and consequences of actions against each other, and making this possible is one of the most essential functions of technology criticism, which we have considered so far. Bringing this consideration to a decision is of course no longer a possible task of science, but of the willing human being: he weighs and chooses between the values in question according to his own conscience and his personal world view. Science can help him to realize that every action and, of course, depending on the circumstances, inaction, in its consequences means taking sides in favor of certain values and thus - what is so often misunderstood today - regularly against others . It's up to him to make the choice."

(1922; pages 149-150)

Value and worldview conflicts in the development of (sub)groups

"There is a dispute not only between class interests, as we are so fond of believing today, but also between worldviews - the truth remaining natural, that which worldview the individual represents depends inter alia, and certainly to a very large degree, on the degree of elective affinity, linking them to a class interest—if only we accept this here as an apparently unambiguous notion. The fate of a cultural age that has eaten from the tree of knowledge is to know that: we cannot derive the meaning of world events from the result, however perfect it can may be read from his research, but must be able to create it ourselves; that world views can never be the product of advancing empirical knowledge, and that therefore the highest ideals, which move us most powerfully, forever affect in conflict with other ideals, that are as sacred to others, as ours are to us." (1922; page 154)

Value freedom of the sociological and economic sciences

"Infinite misunderstandings and, above all, terminological, and therefore completely sterile, arguments have been linked to the word value judgement, which apparently does not contribute anything to the matter. It is quite unequivocal that these discussions are, for our disciplines, practical evaluations of social facts as practically desirable or undesirable from an ethical or cultural point of view or for other reasons. The fact that science wants to achieve 1. valuable results, i.e. logically and factually correct and 2. valuable results, i.e. important results in the sense of scientific interest, that the selection of the material already contains an evaluation - such things surfaced, despite everything that has been said about them, as serious objections. No less the almost incomprehensibly strong misunderstanding has arisen again and again: as if it were claimed that empirical science cannot treat subjective evaluations of people as objects, while sociology and the entire theory of marginal utility in economics is based on the opposite assumption. But it is all about the highly trivial requirement: that the researcher and performer should establish empirical facts (including the evaluating behavior of the empirical people he has investigated) and his practically evaluating of these facts as positive or negative (including any evaluations made by empirical people as the object of an investigation), in this sense: his evaluating opinion, should definitely be distinguished, because these are heterogeneous problems." (1922; Pages 461-462)

Freedom of (ethical) choice unlocks rationality as the only dimension and means of surviving in uncertainty without sacrificing intellectual integrity

"Struggle cannot be cut out of all cultural life. One can change one's means, one's object, even one's basic direction and vehicles, but one cannot eliminate oneself. Instead of an external struggle of hostile people for external things, it can be an inner struggle of loving people for inner goods and thus instead of external compulsion an inner violation (especially in the form of erotic or charitable devotion) or finally an inner struggle within the soul of the individual with himself - it is always there, and often the more consequential the less it is noticed, the more its course takes the form of dull or easy letting-go or illusionistic self-deception or it takes place in the form of selection. Peace means a shift in the forms of combat or the opponents in combat or the objects of combat or finally the chances of selection and nothing else. Whether and when such shifts stand the test of an ethical or other evaluative judgement, nothing can be said in general. (...) Any empirical consideration of these facts would, as good old J.S. Mill remarked, lead to the recognition of absolute polytheism as the only metaphysics corresponding to them. A consideration that is not empirical, but meaningful: a genuine philosophy of values would also, going beyond this, not be allowed to ignore the fact that no matter how well-ordered a conceptual scheme of values would be, it would not do justice to the most crucial point of the facts. Ultimately, it is not just about alternatives between the values, but also about an unbridgeable, deadly struggle, just like between God and the devil. There are no qualifications or compromises between these. Mind you: not in this sense. Because, as everyone experiences in life, they exist in fact and consequently in outward appearances at every step. In almost every single important statement made by real people, the value spheres intersect and intertwine. The flattening of everyday life in this actual sense of the word consists precisely in the fact that the human being living in it is not aware of this partly psychological, partly pragmatically caused mixture of values hostile to death and above all: also does not want to be aware that he has rather the choice between God and the devil and one's own final decision about which of the conflicting values should be governed by one and which by the other. The unwelcome but inevitable fruit from the tree of knowledge of all human comfort is none other than this: to know those opposites and therefore to have to see that every single important action and that life as a whole, if it is not like a natural event glide along, but should be consciously guided, means a chain of final decisions, through which the soul chooses its own destiny, as with Plato: - that means the meaning of its actions and being has been granted again and again, therefore contains the interpretation of this point of view as relativism - as a view of life, which is based on the radically opposite view of the relationship of the value spheres to each other and (in a consistent form) only on the basis of a very special (organic) metaphysics can be meaningfully carried out." (Pages 469-470)

“Politik als Beruf” (Politics as a Vocation)

For Max Weber, passion, a sense of responsibility and a sense of proportion are the most important qualities of a good politician. A good politician is not concerned with money, but lives passionately for his political cause. Weber demands passion in the sense of objectivity: dedication to a "thing", or "cause".

Weber argued that politicians play an important role in the functioning of modern societies, as they are responsible for representing the interests of the people and making decisions that shape the direction of the country. Citizens have the right to hold them accountable through the democratic process. Weber argued that legitimate authority is based on the belief that those in power have the right to rule, and that this belief is reinforced through legal, traditional, and charismatic forms of authority.

Sources:

Weber, M. (1922), Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Wissenschaftslehre, Tübingen.

Weber, M. (1918), Politik als Beruf, in:

Geistige Arbeit als Beruf: Vier Vorträge vor dem Freistudentischen Bund, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot.

Below you can see a video, about Weber's four ideal types of social action, from what I think is a great online course from the University of Amsterdam on classical sociology.