Pyramids for Safety?

𝐖𝐢𝐥𝐥 𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐨𝐫 𝐢𝐧𝐣𝐮𝐫𝐢𝐞𝐬 𝐚𝐥𝐬𝐨 𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐦𝐚𝐣𝐨𝐫 𝐚𝐜𝐜𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐬?

Many believe so.

The longstanding belief that major and minor accidents share similar causes originates from Heinrich’s 1931 accident triangle. Based on insurance claim reviews, Heinrich proposed a ratio suggesting that many minor incidents and near misses precede a major accident. Bird repeated the idea with a new study based on reported incidents and added a level to the triangle, while Salminen presented national statistics in pyramid form. The frequency of minor events was seen as economically significant and potentially useful for illustrating the scale of risk exposure.

But, in 2002, Andrew Hale argued that the belief in shared causes between minor and major accidents is an urban myth. What’s important here is that Heinrich himself did not claim identical causes. He noted variability and randomness in accident outcomes. Subsequent empirical studies and accident statistics show significant differences between minor and major incidents in terms of energy involved, activities, locations, and causal patterns. For instance, in the chemical industry, most lost-time injuries come from mundane activities like walking, which have little relevance to preventing disasters like chemical leaks or explosions.

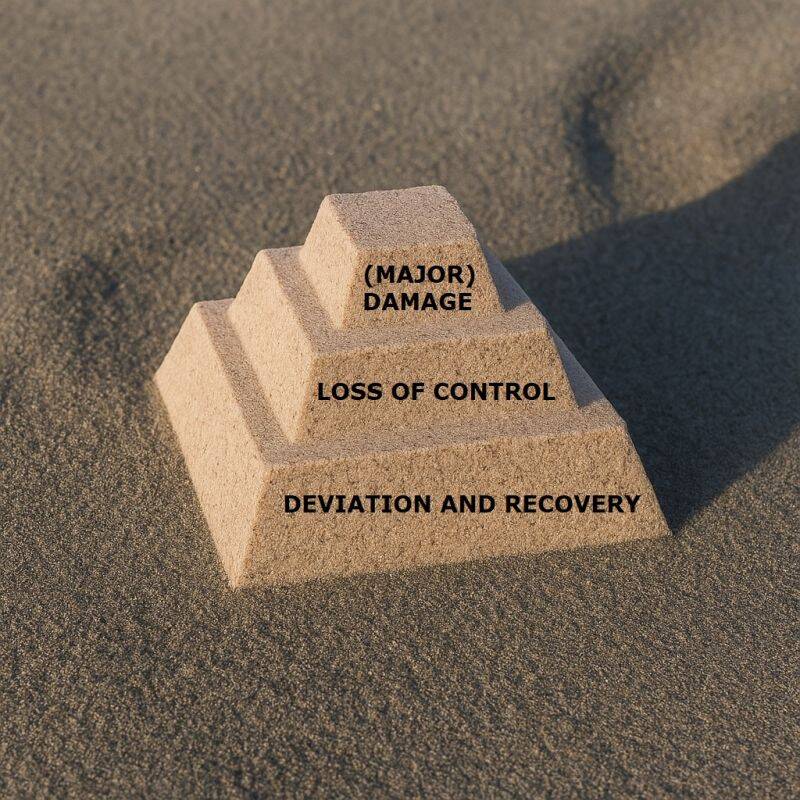

Hale conceptualized accidents as processes with multiple points for potential recovery. Not all deviations escalate into accidents, and not all minor incidents are precursors to major ones. Therefore, the focus should be on understanding specific accident scenarios, instead of comparing outcomes by severity. For this reason, Hale drew a step pyramid like the one in Djoser instead of the smooth pyramid of Khufu in Giza. See my simple reproduction above this piece.

So, while management systems may look similar at a high level, their detailed application must be tailored to the potential severity and nature of specific hazards. Prevention strategies, therefore, should be based on clearly defined, scenario-specific risks. In the meantime, though, we’re still often doing broad management audits and using prevention systems that do not differentiate between control mechanisms for minor and major hazards…

Thanks to Ben Ale for providing this reference, and SWOV for handing me a copy.

Source:

Hale, A. (2002), "Conditions of occurrence of major and minor accidents - Urban myths, deviations and accident scenario's", in: 𝘛𝘪𝘫𝘥𝘴𝘤𝘩𝘳𝘪𝘧𝘵 𝘷𝘰𝘰𝘳 𝘵𝘰𝘦𝘨𝘦𝘱𝘢𝘴𝘵𝘦 𝘈𝘳𝘣𝘰𝘸𝘦𝘵𝘦𝘯𝘴𝘤𝘩𝘢𝘱 15 (2002) nr 3, pp. 34-41.